The Doctor Who Defied Segregation—And Won

Civil Rights and Medicine 101, Lesson one : How Dr. George Simkins Jr. said Enough

In this Lesson, you will learn :

✅ How Dr. George Simkins Jr. fought to desegregate hospitals

✅ How his legal victory paved the way for Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

✅ Why hospital desegregation wasn’t just about morality—it was about federal funding and policy enforcement

✅ Why racial disparities in healthcare persist today

Picture this...

A Black mother rushes her feverish newborn to the nearest hospital, desperate for help. But at the entrance, a nurse shakes her head. "We don’t treat Negroes here." The child is turned away. Hours later, the newborn passes away. Not because there wasn’t a doctor who could have saved her. But because that doctor wasn’t allowed inside the hospital either.

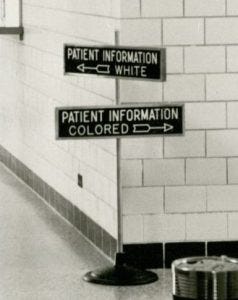

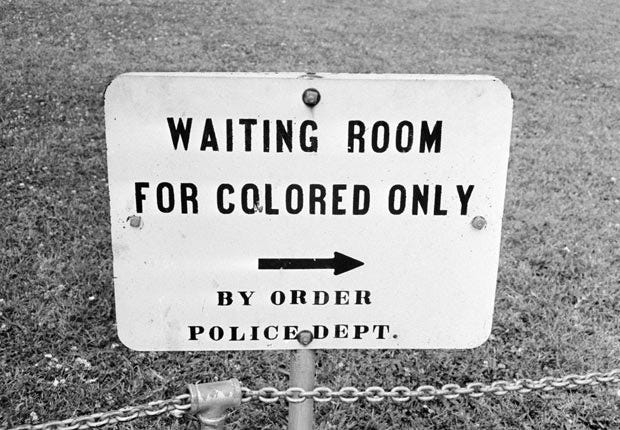

This wasn’t a rare tragedy before the 1960s, it was reality. Across the Jim Crow South, hospitals took federal tax dollars while openly denying Black patients care.

Black doctors who trained for years to save lives? They were locked out of residencies and barred from admitting their own patients to white hospitals. And for decades, the government let it happen.

Until one Black dentist named Dr. George Simkins Jr. said, Enough.

The Forgotten Civil Rights Battle in Medicine

When we reflect on the Civil Rights Movement, the focus is often on voting rights, school desegregation, and fair housing—the landmark battles that dominate history books and classroom discussions.

But what about healthcare?

What about the reality that Black Americans were dying—not because medicine lacked the ability to save them, but because hospitals refused to treat them?

The Medical Civil Rights Movement was one of the most overlooked yet transformative fights of the Civil Rights era.

Despite being one of the most effective racial integration efforts in American history, the desegregation of hospitals is rarely taught in schools.

It is missing from history textbooks, absent from medical, nursing, and pharmacy school curricula, and barely mentioned in mainstream discussions of civil rights.

Why?

Because the desegregation of hospitals wasn’t framed as a moral victory—it was framed as an economic and political issue.

The legal battles weren’t fought on the premise that healthcare is a fundamental human right; they were fought on the principle that hospitals taking federal funds must comply with civil rights laws.

It was federal funding, legal leverage, and economic pressure—not ethical responsibility—that forced the change.

This movement also exposed the deeper systemic inequalities within the healthcare system, revealing how racism had long dictated who had access to life-saving treatment and who did not.

To fully understand racial health disparities today, we must acknowledge this buried history. Because when we fail to recognize the past, we set the stage to repeat it.

And if you’ve been paying attention to the world around you—it’s already happening.

A Law That Protected Segregation

This injustice wasn’t just allowed—it was protected by law.

In 1883, the Supreme Court ruled that private businesses could legally discriminate, even if they were the only hospital in town.

And as long as segregation wasn’t government-enforced, it was untouchable by the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

This meant that hospitals could take federal money, build new facilities, and still refuse to treat Black patients.

And they did. For nearly 80 years.

Until Dr. Simkins changed everything.

The Hill-Burton Act: A Law That Helped—and Hurt

In 1946, Congress passed the Hill-Burton Act, which provided federal funds to build and expand hospitals across the country.

The goal: To ensure that every American had access to healthcare.

But there was a catch.

The law allowed hospitals to receive federal funding while still maintaining "separate but equal" facilities for Black and white patients.

In reality, this meant that Black patients were often treated in overcrowded, underfunded, and poorly equipped hospitals—or denied care altogether.

Even worse, hospitals built with Hill-Burton funds were not required to desegregate, despite using taxpayer money.

Black communities had paid into a federal system that actively excluded them.

So how did hospitals get away with this for so long?

By the 1950s, the federal government had spent billions on hospital construction, yet racial disparities in healthcare were worsening.

But in Greensboro, North Carolina as president of the Local NAACP chapter, Dr. Simkins had seen enough, it was time to hold the health care systems accountable.

He along with several others, sued local hospitals Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and Wesley Long Community Hospital, knowing they weren’t just fighting against local policies

But challenging the entire structure of federally funded segregation.

The Moment That Changed Everything

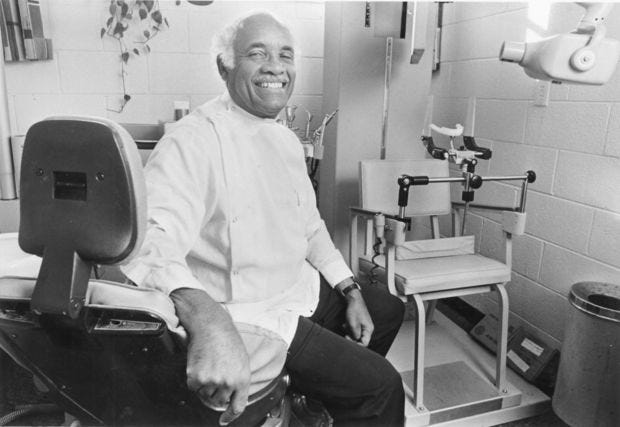

It wasn’t a lawyer or a politician but a dentist, Dr. George Simkins Jr. that became enraged by how his patients were treated.

One night, a Black man came into Simkins' office with a severe tooth infection. If left untreated, it could be deadly.

Simkins stabilized him and then sent him to the nearest hospital for further treatment.

But the hospital had a policy: No Black patients allowed.

The man was denied treatment.

Simkins knew he had two choices: accept this as the way things were—or fight back.

The Lawsuit That Shook the Medical System

In 1962, Dr. Simkins and a group of Black doctors sued Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and Wesley Long Community Hospital in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Their argument? If a hospital takes federal tax dollars, it must serve all citizens.

Sounds logical, right?

But the hospitals fought back, claiming they were private institutions and could refuse service to anyone they wanted.

The first ruling? The courts sided with the hospitals.

But Simkins wasn’t done.

He appealed the decision to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals.

And now, the federal government had a choice:

Side with the hospitals? Or rewrite the rules of American medicine?

The Landmark Decision That Changed Medicine Forever

In November 1963, the Fourth Circuit ruled in Simkins' favor.

This was the first time a court declared that hospitals accepting federal funds could NOT discriminate.

Dr. Simkins, a dentist, had done what generations of Black doctors were told was impossible. He had taken on the system—and won.

This victory would become the foundational win needed to create Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and eventually—Medicare.

Why This Still Matters Today

Please know desegregation didn’t fix everything.

The racial disparities in healthcare today are direct results of decades of segregation and systemic racism:

Black maternal mortality is still 2-3x higher than for white women.

Medical bias in pain management and treatment is still rampant.

Black communities continue to face doctor shortages.

Yet, we must continue to fight for better access for all.

📢 Share your thoughts! Do you think federal funding should still be used as leverage to enforce health equity? Let’s discuss in the comments.🚀

Sources:

University of North Carolina’s Southern Oral History Program Collection

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 211 F. Supp. 628 (M.D.N.C. 1962)

Next Lesson:

Dr. Simkins' case set the stage for something even bigger: Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and the creation of Medicare and Medicaid.

But how did these policies force over 1,000 hospitals to integrate overnight?

And how did they transform healthcare access in America?

🔹 Stay tuned for the next lesson to find out!

🚀 Subscribe for more Civil Rights and Medicine 101!

There is always so much more to learn - I had no idea it was a dentist who pushed for this case! Thanks for writing this.